Funeral Culture out of Scratch: Body Disposal Practices in the Soviet Union

Vorgestellt wird das Projekt im Rahmen des Osteuropakolloqiums am 04.11.19 um 18 Uhr an der Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder), Große Scharrnstr. 59, HG Raum 217.

The set of radical transformations of social sphere, which had followed the Bolshevik Revolution, became an important research topic among the scholars all over the world right after the Revolution, and keeps vibrant interest up until now. Total opposition to the “old worlds” indeed became the core of Bolshevik discourse and practice during the 1920th. Bolshevik ‘revolutionary dreams’ depicted new utopian visions of the past, which included all kinds of innovations from communal living up to new Soviet family rituals.

However, the real revolutionarityof the Bolshevik project could be doubted. The quick shift to much more traditional attitudes (such as in family low, school system, passports, etc.) in 1930s, which followed the experimental period of 1920s was widely studied before. But even some of the most revolutionary experiments of 1920s could be considered as a continuation of pre-revolutionary trends. This project aims to reveal this trend on the basis of the transformation of body disposal practices. Due to the general marginality of the funeral practices, they were never on the edge of the Bolshevik political struggle, however, these transformations could be used as a good source to follow deep continuation of the transformations in Soviet Russia.

Despite the desire of the Bolsheviks to control and change all aspects of human life, the question of what constitutes human life and death, as well as what the funeral ritual should be and what meanings it should express in many respects remained open. While there was no clear understanding how to deal with the ‘ordinary’ death there were a number of issues in pre-revolutionary funeral system that were absolutely unacceptable for Bolsheviks. The most important among them were social-estate principle underlying funeral practices and the dominance of the Orthodox Church. The Decree on Cemeteries and Funerals of the RSFSR Council of People's Commissars (dated December 7, 1918) abolished the grave categories and put all cemeteries, crematoriums and morgues as well as funeral arrangement under control of local Soviets. This Decree cancelled all burial charges and introduced equal funerals for all citizens. It was noted, however, that relatives might perform religious ceremonies on their own will and at their own expense (SNK, “Dekret O kladbishchakh,” 163 - 4.)

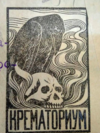

The funeral reform as a part of the separation of Church and State Bolshevik policy pursued three main objectives. The first goal was to deprive the Church of control over burial proceedings and burial revenues. Thus the Church would lose an essential source of revenue and non-religious funerals could be legally introduced. Secondly, to cancel burial ranking, that is to make funerals uniform and affordable for all. The third objective was to introduce cremation consistently opposed by the Church. The funeral reform brought some important changes in funeral administering. Death registration procedure was devolved to Soviets of Deputies and civil registry offices, which proofed the management transfer announced by the Decree on civil marriage from December 18, 1917. Grave site charges in cemeteries were completely voided. Service fees previously to be collected by funeral homes and by clergy were replaced by the minimum necessary service payment (coffin manufacture and grave digging) at a Soviet of Deputies or by presenting a social insurance order. The confessional specifics of cemeteries were completely eliminated: now any person regardless of his/her religious convictions or absence thereof could be buried in any cemetery.

The project of the funeral reform of 1918, although it looked extremely radical and based on the ideas of atheism, in fact largely inherited the trends in funeral practices that took shape in church and secular circles of Russia before the revolution. However, the Decree on Cemeteries and Funerals may be also considered in the wider context of the European modernization discourse. Though the experience of all European countries was important, the most influential was considered German. During the implementation of cremation project in Soviet Russia, civil engineers and hygienists were sent to Germany to obtain the experience, the incinerators for the first Soviet crematorium were exported from Germany as well.

The aim of this project is to reveal other point of reference between Soviet and German funeral cultures during 1917–1935. The new data, obtained in German libraries and archives, will be used in my book “A new death for a new man: funeral practices in early Soviet Union”, which is to be published by the “New Literary Observer” publishing house in year 2022.

Dr. Anna Sokolova is a Research Fellow at the Department of Russian Nation at the N. N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, and a Lecturer at the Master Program “History of Soviet Civilization” at the School of Social and Economic Sciences (MSSES). She graduated from the Department of Philosophy at the Lomonosov University Moscow and defended her PhD Thesis “Transformation of the funeral rites of Russians in the 20th– beginning of the 21stcenturies (on the materials of the Vladimir region)” in 2012 at the Russian Academy of Sciences. In 2015-2016 she was a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at the Bowling Green State University, Ohio and the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University. Her publications and ethnographical research deal with the funeral culture in Soviet Union and Russia, popular religiosity, urban rituals and memorialization of war conflicts.