Pranksters who play practical jokes on others, make (almost) everyone laugh, and get away with it, are universally known. That there is someone else besides Till Eulenspiegel to whom this description refers might be less obvious, as he practically dominates the droll story as a symbolic figure. Sina Kobbe is a German philologist. At the Institute of German Studies, she researches Hans Clauert, a relatively unknown prankster, who is said to have played his tricks in Brandenburg in the 16th century. Kobbe is sure that rescuing him from oblivion could radically change the perception of the droll story.

He lies, spoofs, cheats, teases, steals, and banters. His name is Hans Clauert, but hardly anyone has heard of him. His existence is overshadowed by the omnipresent Till Eulenspiegel to whom he owes his nickname “Eulenspiegel of the Mark” – and thus, in some measure, even his meagre fame today. The prototype of the traveling joker is known almost everywhere. With the first publication of “Dil Ulenspiegel” in 1510, his tricks became known all over Germany. But not only there: over the centuries, the 96 stories were translated into about 280 languages.

“Better” than the original?

In fact, it is entirely possible that Till Eulenspiegel as we know him today – from one of the dozens of compilations and retellings by modern authors such as Erich Kästner – has much more in common with Hans Clauert than with the original “Ulenspiegel”. After all, Ulenspiegel was a lot more malicious than today’s collections of Eulenspiegel stories want us to believe. “The original Ulenspiegel is often mean for no reason, and in some of the stories people get seriously harmed,” says Kobbe who has made the droll story the focus of her research. “Just like Ulenspiegel, Hans Clauert plays practical jokes on his contemporaries. And just like him, he always acts in his own interest, especially when it comes to his physical comfort. But what he does is always harmless, sometimes mundane – and nobody really gets harmed.”

Thus, Clauert’s social position differs considerably from that of his more prominent counterpart: Eulenspiegel is an outsider, a traveler without obligations who wants to move on, but also has to, as he leaves behind a trail of scorched earth wherever he goes. He pretends to be someone else, takes on roles, hires himself out, and does mischief until he has no other choice but to take to his heels. By contrast, Clauert comes from a middle-class background, is married with a stepson, and works, first as a locksmith, then as a salesman. And he is rooted in his native region of Trebbiner Land where the majority of the 34 stories about him are set. Everybody knows him, everybody loves him, as the foreword states. “Most of the stories about Clauert’s pranks end with a laughter that creates commonality.”

Like the one in which Clauert is dragged to court by his own wife. The couple fell out with each other, and his wife sued him. So the notorious joker has to appear before his sovereign, the elector, in the capital of Berlin where he is eventually given an envelope to hand over to the captain of his town. What Clauert does not know: It is a warrant of arrest according to which he has to go to prison. But the unsuspecting messenger smells the rat. As he is unable to read the letter himself, he has it read to him – and, without further ado, throws it into the river Spree. Some time later, on a visit to Trebbin, the elector asks the captain how Clauert is doing in the dungeon. As the captain does not know about any of this, the elector sends for the prankster and confronts him. Clauert answers – truthfully – that he threw the letter into the Spree while still in Berlin to ensure it would arrive in Trebbin before him, and the message is delivered as quickly as possible. The elector likes the reasoning so much that he laughs heartily – and puts Clauert under his protection from then on.

Unlike Eulenspiegel, who has to fear the authorities all his life, Clauert plays tricks on “his” elector and the Trebbin captain without ever getting into trouble; and sometimes he even acts on their order. Despite his middle-class background, Clauert has a waggish sense of humor. “He takes on the role of the court jester without being a fool,” Kobbe says.

The stories about Clauert tell his life – from cradle to grave. Even during his training, he reveals his sense of humor and plays a trick on his master. His travels take him to a count’s court in Hungary. Later, the approaching Turks make him leave. After that, he leads a dissolute life with gambling and drinking, gambling away all his money. Only then he returns home, marries, and settles down. The marriage is by no means harmonious, but lasts until he dies. His wife also fulfills his last wish and buries him among the townspeople, not the peasants.

Rediscovered as a regional copy

But did Clauert actually exist? According to Kobbe, it cannot be ruled out that there was a man like Clauert in Trebbin, someone who behaved foolishly, but cleverly joked his way through life. Presumably, such jokers were to be found in many towns. “But it is not often that they are commemorated in literature,” she says. “The names of most of them are forgotten – so they ‘became’ Eulenspiegel, or their stories were attributed to him.”

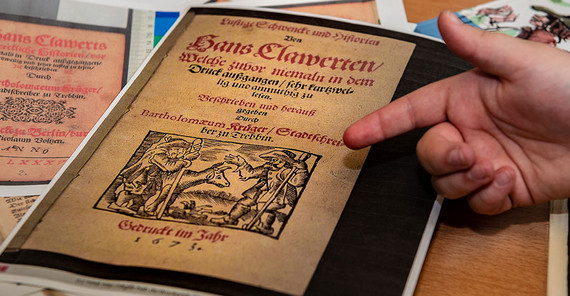

But not so Hans Clauert, whose tricks made him a regional literary celebrity – thanks to Bartholomäus Krüger, the town clerk of Trebbin. In 1587, Krüger published the first issue of “Hans Clauerts werkliche Historien”, eight more issues had followed by the 17th century. In addition to the official versions, there were certainly many informal issues, so-called fair printings, that were sold in large numbers, but of which no copies have survived. Definitely a success story, in Kobbe’s opinion. “Clauert was very well-known in his time. The quick succession of reprints indicates that his stories were well received and the book was no slow seller.” Nevertheless, he eventually fell into oblivion and was rediscovered and re-issued only in 1850 – for the first time with the addendum “the Eulenspiegel of the Mark”. Was it just a marketing ploy? “At any rate, it was an economization.” Since then, the nickname has become inseparable from him. Later adaptions such as by Klabund or Johannes Bobrowski took on the comparison.

Researchers, too, have mostly studied the book in connection with Eulenspiegel. Kobbe intends to change this, so she is examining the stories about Clauert thoroughly. First of all, she traced down their various editions. Fortunately, the first edition has been digitized in the meantime and was easy to obtain; others are more difficult to get hold of. Their trails lead to Poland and Russia. So far, Kobbe has located 4 of the 9 editions.

“I research character constellations and references to regional history in the texts, as well as the history of their literary reception.” The ultimate goal is the proper classification of the work in literary history. In particular, Kobbe wants to work out how much Clauert – as a figure, but also in his works – differs from “Ulenspiegel”. “There are two major differences: For one thing, Clauert is comparatively harmless, his tricks are not evil.” And for another, the author distances himself from the prankster. Even though Krüger licenses him to play tricks, he does not approve of them. All texts end in a rhymed “moralisatio” – a kind of interpretation and appraisal of the story – which clearly tells the reader: This is funny, but immoral. Don’t repeat any of it!

Rewriting the history of the literary genre

With her research, Kobbe not only intends to bring Clauert out of the large shadow of Till Eulenspiegel. She is also confident that her research has the potential to change the overall picture of the droll story. “One of the most famous monographies on the droll story is titled ‘Die Freude am Bösen’ (The Joy in Evil).” This may well be true for Eulenspiegel, but not for Clauert. In this way, I hope that my analysis of the understudied Clauert may lead to a reappraisal of the whole genre.”

Kobbe’s own journey to research was not very straightforward: While writing her examination paper at the end of her teacher training at Mannheim she discovered that poring over volumes and papers in libraries and archives was what she really wanted. When in one of her last lectures she heard more about droll stories, it just clicked – even though the droll story does not enjoy the very best reputation in literature history and studies. “For a long time, the texts were considered unliterary. They are everyday stories, often not very subtle, rather crude, even the illustrations, as quite a number of woodcuts in the ‘Ulenspiegel’ show piles of muck.” This does not bother Kobbe. “I quite like the genre. It is down-to-earth and funny – and breaks with the common image of the stuffy Middle Ages.”

Kobbe has made it her mission to give Hans Clauert, the “Eulenspiegel of the Mark”, greater visibility. Currently, she is preparing her doctoral thesis under the supervision of Prof. Dr Katharina Philipowski and Prof. Dr Stefanie Stockhorst. There is still a lot of work to do, Kobbe realized soon after changing to the University of Potsdam: In her first semester, she offered a seminar on the droll story. “I expected that Hans Clauert, the hero of the Mark, would be a household name here. I was wrong, but I will remedy that!”

At least Clauert’s home town of Trebbin remembers him and proudly adopted the name of “Trebbin, the town of Clauert.” A library, restaurants, and hiking trails have been named after him, and a Clauert statue was set up in the market square. And several times a year, the husband of the deputy mayor dresses up to impersonate the perhaps funniest son of the town.

Little is known about Bartholomäus Krüger, the author of “Hans Clauert”. What we know is mostly from his own words in the prefaces to the various editions of his bestseller. The only documentary evidence of his existence is a certificate of matriculation from the University of Wittenberg. So Krüger must have been an intellectual, as is evident from his “Clauert”: The author mentions legal decrees and knows a thing or two about history. As he was familiar with the region around Trebbin, it seems that he came from there, or at least lived there. In his own words, he was Trebbin’s town clerk and organist – a church man. This also shows in his texts where he combines entertainment with sharing his religious thoughts. Today, it cannot be said for sure whether the stories of Hans Clauert are partly autobiographical or not.

Droll stories are a small literary genre with a long tradition. They were most popular between the 13th and 16th centuries. The German word for droll story, Schwank, is derived from the Middle High German “swanc” for “funny idea”. Droll stories are generally crude and funny, and were often published in compilations. The best known representatives of the genre are Amis the Parson, the Parson of Kalenberg, Neithart Fuchs, The Citizens of Schilda (“Die Schildbürger”) – and, of course, Till Eulenspiegel.

The Researcher

Sina Katharina Kobbe studied German, history, and philosophy/ethics at the University of Mannheim with the aim of becoming a secondary school teacher. She has been writing her PhD thesis under the supervision of Prof. Dr Katharina Philipowski since 2017. When her supervisor was awarded a Professorship in German Medieval Studies in Potsdam in 2018, Sina Kobbe also moved to Brandenburg.

Mail: kobbeuuni-potsdampde

This text was published in the university magazine Portal Wissen - Two 2019 „Data“.