Later, the teacher brings the slim, pale-faced child to the blackboard and lets her solve one of the most difficult tasks in writing. Everyone will be able to see that the girl can do arithmetic like no other in this fourth grade. Karkokli is satisfied. She knows all too well how it feels to have to think in a language that is not your own and whose words sometimes just fly away when your thoughts are elsewhere. Maybe to the family at the new home in the German city of Wittenberge on the Elbe. But perhaps also to the home in Syria, in the almost completely destroyed city of Deir ez-Zor on the Euphrates.

Karkokli was in her early twenties when she completed her studies to become an elementary school teacher at her hometown university and took over her first class in a small village. She will never forget the moment when the children looked at her with wide eyes, that one first moment when she understood that she was now responsible. This honest, completely open, completely genuine feeling between her and the children. Wherever she stands in front of a class, she remembers this feeling and senses the great happiness of having chosen the right profession.

From Syria to Wittenberge

This is probably why she made a beeline for the school when she arrived in the Brandenburg town of Wittenberge in 2015 at the end of her long flight from the war in Syria. “I wanted to make myself useful. I talked to the Syrian parents who brought their children to school and translated from English into Arabic.” When someone told Karkokli to apply for a completely new qualification program for refugee teachers at the University of Potsdam, the young teacher did not hesitate for a second. With a German degree, she would perhaps be able to work in her profession again. Nothing interested her more than that.

Every day she took the train from Wittenberge to Potsdam, three hours forth and three hours back, crammed the foreign vocabulary in intensive courses and heard in seminars how the German school system differs from the Syrian one and what is done differently pedagogically in Germany. In her professional practice, the young teacher did not feel like a stranger for a minute. Psychologically, she even found herself a little more thoroughly trained in Syria. “Teaching children something, responding to them, developing a sense of how to support them well is universal,” she says, “and perhaps it is the same all over the world.”

In just three university semesters, she raised her language level from zero to B2, and at the same time completed all the teacher training courses she needed for the certificate to be able to return to the Friedrich Ludwig Jahn Elementary School in Wittenberge as an assistant teacher. More than 50 girls and boys, refugees like herself, sat there in German classes and did not understand a word. Karkokli found this completely counterproductive. With Mazen Houkan, a Syrian colleague and a specialist in German as a second language, they formed a team, divided the children into three groups and taught them math and music, English and art, sports, and German. “For some of them, it was the first time that they were able to attend school at all,” reports Karkokli, and tells the story of an eleven-year-old boy from Afghanistan who could neither read nor write.

Principal Kerstin Schulz was happy about the assistant teacher positions, which were financed by the Ministry of Education for two years. But she was even more pleased to be able to have the two Syrian teachers in the classroom because the number of children with a migration background continued to increase. “It is so important that there is someone who speaks their language, who helps them to find their way in the foreign culture, who understands the worries of their parents and can clear up misunderstandings.” For example, that the children cannot simply stay at home during the Muslim holiday of Eid, but that they must apply for a school exemption. Or that it would be good if they ate and drank a little during Ramadan to be able to concentrate better in class. The Syrian teachers always found the right words in these situations.

Eventually a permanent contract

Given all this, it was all the more incomprehensible why it should end after two years. “The funding of the positions expired. I was only allowed to work as a pedagogical assistant.” Karkokli was rankled by this – a setback that she did not simply accept. When the school authorities explained to her that she had to have a C1 language level to be employed as a full teacher, but that there were no courses in Wittenberge, she taught herself the difficult grammar and the extensive vocabulary. “But even this certificate was not enough,” Karkokli recalls. Although she had completed a teaching degree in her home country, qualified for the German teaching profession in Potsdam, and had been working as a teacher for several years, she was once again sent to teacher training seminars for career changers. When that was also done and all the degrees were on the table, there should have been no apparent reason not to hire her permanently. “Instead, I worked on temporary contracts in two different schools. That bothered me.” The young woman began to put down her foot, spoke out in public discussions, made herself heard in politics. With a lasting effect: finally, a permanent contract.

In 2021, Karkokli took over a fourth grade class from a colleague whom she had previously been allowed to accompany as an assistant teacher. Principal Schulz was convinced that she was able to do it but feared that there could be objections from German parents. But quite the opposite. Just as she won the hearts and trust of the children from the very first moment, the parents also felt that this was a teacher who was clever and experienced in her profession. The way she challenged without exerting pressure, the way she spurred on and pushed forward without leaving anyone behind, earned her respect.

With this perseverance, Karkokli also mastered her biggest challenge so far last year: the transition of her class to secondary school. “I had to write reports, coordinate things with other teachers, and explain the recommendations to the parents.” She takes a deep breath and breathes out again audibly when she talks about it. In the city’s cultural center, she stood on stage, gave a speech, and handed over her first graduation certificates. “The parents applauded and the children gave me a drawing in which each of them was depicted as a hard-working ant.” She claps her hands together. And then she talks about seeing the boy from Afghanistan on the street again – the one who, at the age of eleven, could not read or write a word and whom she had taught immediately after his arrival. He was now studying at high school and had a three in math, he said to her. And he added: “You did that!”

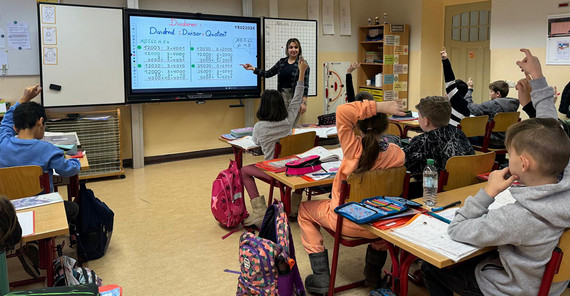

Entisar Karkokli is a teacher. One of the most important professions, wherever you are in the world. She stands in a German classroom and writes numbers on the blackboard that are called Arabic. In her class sit seven children with a migration history. One of them has only been here for a year. A girl from Syria who on some days needs someone who can say “saba tarb saba”. Just for a moment of reassurance to be able to take the next steps all the more easily.

In the spring of 2025, Karkokli, now a German citizen, became the first graduate of the Refugee Teachers Program at the University of Potsdam to receive a civil servant certificate of the Federal Republic of Germany.

This text was published in the university magazine Portal - One 2025 “Children”.