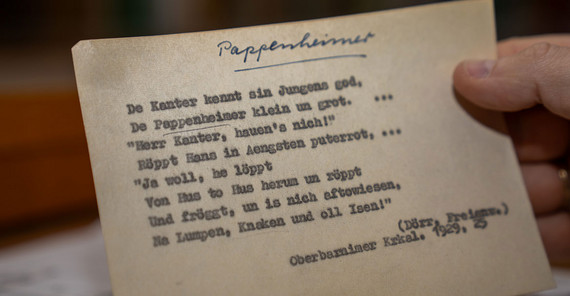

Hardly anyone would know what to do with “Brummküsel”, “Koppskekel”, and “Schlödelblom” (humming top, forward roll, and primrose) if it weren’t for the online portal of the Brandenburg-Berlinisches Spracharchiv (BBSA) at the University of Potsdam. It collects hundreds of thousands of colloquial nouns and verbs, but also idioms and childish counting rhymes. “Een, twee, dree, de Koder löppt in Schnee und du bist free” (one, two, three, the dog is walking in the snow and you are free).

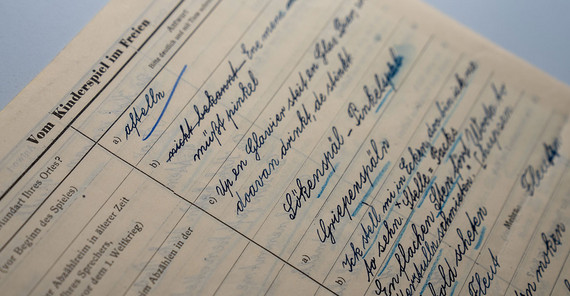

They were written down in the 1950s, when the German Academy of Sciences asked local speakers at more than 2,000 school locations for information – August Höhne was one of them. For decades, these questionnaires were stored first in containers, later in the cupboards of the Department of German Studies.

Diligent work on the flat screen scanner

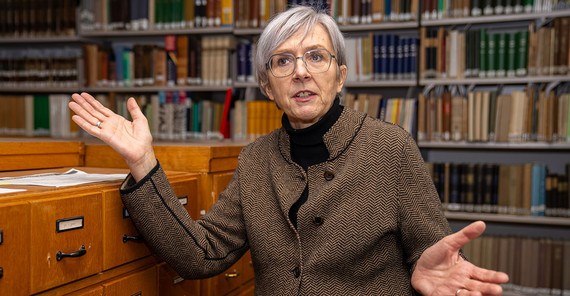

In 2017, a team led by Ulrike Demske began to rouse the archive from its philological slumber and digitize the existing 22,153 questionnaires. A six-year Sisyphean task, says Demske, Professor of History and Variation of the German Language. “At times, four student assistants were busy working on it at the same time. Each of these questionnaires was scanned page by page and correlated with a data set.” In addition, there are audio recordings of people reading texts in dialect. From Abbendorf to Züsedom, the dialect diversity that existed in Brandenburg until the middle of the 20th century is now accessible to the public.

Some of the terms queried in the past have been forgotten in the current of time because no one makes pipes out of willow bark anymore, for example. The fact that even animal names such as “Piermrad” (earthworm), “Pfuhlpieper” (polliwog), or “Pißmier” (ant) sound like fantasy language to our ears has more to do with the linguistic leveling that began with the triumph of the standard language but also of the Berlin dialect. “Think of all the Berliners who have moved to the surrounding region,” Prof. Demske says. “From a linguistic point of view, it is a bit sad that the regional differences are being lost. That’s why the archive is great, because we can look up what it was like in the middle of the last century.”

Findings from dialect research

Although the language archive is limited to the borders of the state of Brandenburg, the dialect does not end at this border. "Rather, the transitions are seamless,” says Luise Czajkowski, research assistant at the department. “The north is oriented toward Mecklenburg, where, for example, the participle with ge- is completely omitted: Ik heb spielt (I have played). Today, due to the Berlin influence, the je- is widely catching on: Ick hab jespielt. In the east, especially in Lower Lusatia, we still have Slavic influences. We see a very large variance within this language area.”

The hodge-podge has a long tradition in Brandenburg: the settlers who moved to the former Slavic territory brought their West Low German and Flemish language with them. In the course of history, Low German also mixed with the French of the Huguenots and with the dialects of displaced persons, including those from East Prussia.

The spoken word is correspondingly multifaceted when comparing it within Brandenburg. “Until the middle of the last century, there was an incredible variety of pronouns alone,” Czajkowski says. “There’s ick or ich, jau, ji and jei, juch, eich or euch[SV1] . The change of language can also be traced on the basis of the questionnaires: The word ‘doof’ (stupid) also meant 'deaf' in Low German. ‘Ick bin doch nicht doof’ meant something like: I’ve understood what you said.”

How the language archive supports research

The linguists estimate the physical inventory of the Brandenburg-Berlinisches Spracharchiv to be 1.5 million index cards. The paper housed on the Campus Am Neuen Palais dates back to the 1920s, when the philologist Hermann Teuchert set out with pen and notebook to write down dialect words up and down the region. In addition, there are the questionnaires from the 1950s and about 100 audio recordings from the 1960s and 1970s. The Brandenburg-Berlin Dictionary was also created from this raw material until 2001.

On the one hand, we owe the past philologists’ passion for collection some finds such as the “Quasselguste” (a talkative person). On the other hand, the other characteristics of spoken language – sentence structure, sound formation, prefixes and suffixes, pronouns – were somehow neglected. “Fortunately, at that time it was not only words that were recorded, but sometimes also entire sentences so that we can continue our research with them today,” says Luise Czajkowski, who is conducting her own research projects on the use of dialect with students.

Once again, they are looking for people from Brandenburg who are able to represent the dialect of their place of residence. “We have data from the 19th century and from the middle of the 20th century. With new data from the 21st century, we can look at what has happened since then. Which forms prevail in the area and which disappear,” Czajkowski explains. “The word 'Icke' (dialect for ‘I’), for example, is still doing very well.”

The Brandenburg-Berlinisches Spracharchiv (BBSA) of the University of Potsdam

Ulrike Demske has been a Professor of German History and Variation of the German Language at the University of Potsdam since 2011.

This text was also published in the university magazine Portal - One 2025 “Children”.