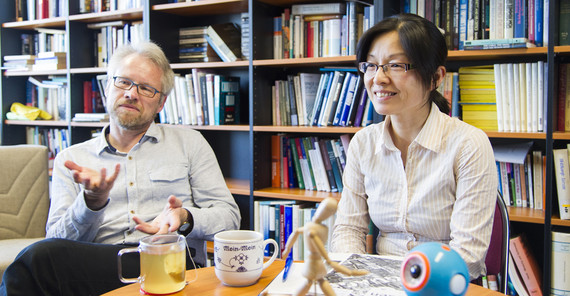

Henry is tall, dark-haired, and has a gentle expression. He knows our favorite songs and tells jokes that make us laugh. Henry is not a man; he is a robot designed by the U.S. firm Realbotix to be an intimate partner for humans. Psychologist Yuefang Zhou and cognitive scientist Martin Fischer visited the company in San Diego, California. Together they are examining how intimate partnerships with robots could determine our future.

Realbotix is a subsidiary of Abyss Creations, a company that has manufactured realistic dolls since 2000. Hair color, body shape, and body size are all tailored to each customer’s preferences. Prices start at $11,000. Most buyers are from Canada and Germany. But while these dolls can neither move nor talk autonomously, the newly developed robots are equipped with artificial intelligence (AI).

In research, AI is the ability of machines to solve problems. So far, Henry can only move his head and speak short sentences; his AI is limited, but this will change soon. “The company’s objective is to create artificial bodies for intimate relationships,” Zhou tells about her talk with company founder Matt McMullen. “In the future, there could be love robots around the world for lonely people with social hindrances.”

The social interest in interactions with robots is huge

Studies carried out at Stanford University revealed that we react emotionally when touching a humanoid robot: our hearts beat faster, and we start sweating and even blush. These are the reactions that Zhou and Fischer want to capture experimentally. Imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could also give us some clues about what is going on in our brains when we interact with a robot. “In fact, there is tremendous interest in interactions with robots in society,” Zhou explains. “But so far there is hardly any empirical data on this topic. They are urgently needed.” Over the past two years, Zhou, who is a researcher from the University of St Andrews, has been a visiting scholar in Martin Fischer’s group. In late 2017, Zhou and Fischer held an international workshop on intimate relationships with robots at the University of Potsdam. A book on the workshop proceedings will be published. The workshop also helped the initial research questions to be formulated for the planned study, for which the researchers are currently seeking funding.

Zhou has also very recently been involved in a sexual medicine project at Charité - University Hospital Berlin. Together with sexologists, the psychologist is looking into whether robots might be able to help to prevent crime. The idea is to see whether potential sex offenders can be treated by getting access to child-sized robots. “It might be possible that learning experiences with humanoid machines reduce inappropriate sexual behavior,” Zhou states. “However, the opposite might happen as well, and the interaction with a childlike robot could intensify pedophilic desires.” To find out more, researchers will first conduct interviews with test subjects, experts, and affected people at the University of Potsdam. They will then also conduct experiments to find out how humans physiologically react to human-robot touch interactions.

Zhou and Fischer are interested not only in sexual interactions with robots, but in particular in the emotional attachment to humanoid machines – which may, in fact, be even positively received and fueled by care and affection. So it comes as no surprise that robotic pets are being increasingly used in the care sector, from plush seals to purring cats. Today, robotic pets are equipped with sensors to register touch and voice; they move autonomously and make some noises. They are said to have a soothing effect on people with dementia, for instance. This said, robots as autonomous companions are probably still far away. Especially in the interaction with vulnerable people, they may become a hazard, since they are not yet flexible enough to meaningfully adapt to unforeseen situations.

The abilities of a robot are crucial to human perception

For many years, cognitive scientist Martin Fischer has been exploring the cognitive bases of interactions between humans and robots. From 2008 to 2011, he researched cognition- and perception-related patterns in the human brain at the University of Dundee for use in programming the iCub robot. Since 2004, researchers from all over Europe have been contributing to the open-source project to develop a humanoid machine able to learn about human cognition, optimizing the abilities of robots. iCub has the dimensions of a 5-year-old child; it has 53 joints, speaks, sees, and hears. Soon it will be equipped with the sense of touch as well. What Fischer was particularly interested in at the time was the interplay between perception and movement: When do we grasp a cup with the right hand and when with the left, for instance. How do robots learn that boxes can be stacked but not balls? How is a shovel used? How about a rake? Answering such questions is essential if robots are to be integrated into our daily lives as seamlessly as possible.

Fischer thinks that the abilities of robots are now more important than their external appearance in interactions with humans. “Our nervous system is highly sensitive to social signals,” Fischer explains. “We are able to discern human faces even in abstract representations of them. So, robots do not need to look particularly humanlike to trigger interaction: Often, two dots resembling eyes will do. And a robot which is clearly identifiable as a machine has another advantage – a less humanoid robot is hardly perceived as uncanny. One explanation for it is the “uncanny valley” effect formulated by Masahiro Mori some 50 years ago: The more similar robots are to humans, the more we accept them – but only to an extent. Too much similarity makes them seem eerie.

Robots present challenges for a society

Sophia is a particularly uncanny robot. The humanoid machine might be confused for a flesh-and-blood woman were it not for her transparent skullcap with all the cables, printed circuit boards, and blinking lights. Sophia has the highest artificial intelligence of any robot at the moment. She is able to adapt to specific situations – she learns. “Sophia is at the cutting edge of technical developments,” Fischer explains. “She can recognize problems, analyze them, and react accordingly. Since 2017, the humanoid machine has held Saudi Arabian citizenship. What sounds like a joke foreshadows the difficulties we might one day face in living with humanoid machines.

“When it comes to robots, social, ethic, and legal issues need to be addressed as well,” Zhou states. What will happen if we perceive robots more and more as human, given that their reactions surprise us and give us food for thought, that we learn from them, or that we enjoy their company – because we love them? What will happen if artificial intelligence is such that we treat robots no longer as objects but as people? Would it mean that we created slaves without rights? The world of science fiction has long explored such dystopias and imagined the uprising of these slaves, who turn against humans and stand up for their freedom. If you take these gloomy visions seriously, the legal fundamentals need to proceed technological developments.

In that sense, humanoid machines pose challenges to experts in many fields. This is what fascinates Fischer and Zhou the most about interrelations between robots and humans. The topic attracts not only cognitive scientists and psychologists but also lawyers, philosophers, computer scientists and linguists. “Research on the interactions between human and machine is a multidisciplinary task,” Zhou concludes. Only together can researchers get closer to finding an answer to one fundamental question: “Research on robots can help us understand what makes a human being a human being.”

THE RESEARCHERS

Prof. Martin Fischer, Ph.D., studied psychology and has been Professor of Cognitive Sciences at the University of Potsdam since 2011.

martinfuuni-potsdampde

Yuefang Zhou, Ph.D., studied psychology at the University of Dundee in Scotland. From 2016 to 2018, she has also been a visiting scholar in Cognitive Sciences at the University of Potsdam. Since 2017, she has also been affiliated with the Institute of Sexual Science and Sexual Medicine at Charité - University Hospital Berlin.

yuezhouuuni-potsdampde

Text: Jana Scholz

Translation: Monika Wilke

Published online by: Marieke Bäumer

Contact to the online editorial office: onlineredaktionuuni-potsdampde