Misinformation from the White House

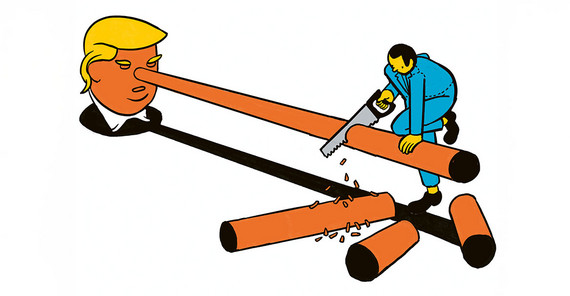

On January 21, 2017, the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration as President of the United States of America, outrage spread. The newly sworn-in president announced that more people than ever before had watched the ceremony on the National Mall. However, photos circulating on Twitter clearly showed that there were barely half as many people as four years earlier at Barack Obama’s inauguration. When various media outlets refuted the claim, Trump’s press secretary Sean Spicer accused them of deliberately reporting false information. Trump himself spoke of “fake news.” The farce, which many people initially found amusing, was only the prelude to an almost endless flood of claims, more or less obvious lies and misinformation, and accusations of “fake news” with which the US president bombarded others. The Washington Post kept track and counted 30,573 false or misleading statements by the end of his first term, around 21 per day. He spread many of them via his account on the social media platform Twitter, which in the meantime seemed to become the unofficial mouthpiece of the White House. This flexible relationship with the truth did not harm Trump. On the contrary, he was re-elected in 2024 and has been US president again since January 2025. He has also been active on X again since 2022, after being temporarily banned following his election defeat in 2021 for false statements and calls for violence. Today, more than 100 million people follow him there – 20 million more than in January 2021 – making him one of the top ten most successful accounts worldwide.

Twitter is – at least until now – also a preferred research source for Prof. Lewandowsky. “For a long time, the social network was very productive for our research: the data was extensive and easily accessible. It allowed us to reconstruct how communication works on the platform.” Since Elon Musk took over Twitter and renamed the platform X, things have changed. X has made it more difficult for researchers to access the data, setting the project back by about a year. The team has since fought for access, citing Article 40 of the European Union’s Digital Services Act, which guarantees researchers access to research data in the event of potential systemic risks. This refers to dangers to democracy and its foundations that could arise from digital social networks. For example, when communication no longer allows for controversial but respectful discussions at eye level, but is instead characterized by hate, insults, and lies.

Of course, these have always existed, Lewandowsky says. In 2003, for example, the United States and Great Britain claimed that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction, thus legitimizing the Iraq war. “Although these were never found, a third of Americans still believe today that they existed,” he says. “Back then, I began to examine how misinformation spreads and what impact it has from a cognitive science perspective. Even before social media existed.”

Emotionality instead of facts

Social networks such as Facebook, X & Co. have long been actively promoting the spread of misinformation or even lies. “The reason for this is the algorithms with which the platforms select which content has the greatest reach,” the researcher explains. “And these are precisely those that generate attention by arousing outrage, fear, or hatred. Like misinformation, which is often more blatant and disturbing than facts – and is therefore preferred by algorithms since they don’t care about the quality of information.” It has been shown that people stay longer on these platforms when they are shown content that evokes negative emotions. And this finding fuels the business model of the currently most successful social networks: those who stay longer see more advertising, with which the companies earn their money. “We know from whistleblowers that Facebook highlights outrageous content five times more often than positive content. The consequence of this is that people are polarized and imbued with hatred.” However, the tech companies are not accountable for this, at least not to the users. “The online market is fundamentally different from all other markets,” Lewandowsky says. “The big social media companies do not have a business relationship with the people who use their platforms, but with their advertising customers. Therefore, the negative consequences for users are considered collateral damage, at least potentially.”

However, democracy and the way in which societies communicate and discuss issues have long since been damaged. Social networks are shifting the value of information away from facts and truth toward emotions and (apparent) authenticity. “With the help of social networks, figures such as Donald Trump have succeeded in redefining truth and honesty so that these are no longer based on evidence and accuracy, but on emotionality and sincerity,” Lewandowsky says. “Although he lied constantly during his first term in office, he was considered honest by his voters because he sincerely expressed his convictions.”

And it’s getting worse: Not only do social networks promote the dissemination of misinformation, but they also make it increasingly difficult to combat it. Social media and other digital media have caused our attention span to shrink: people’s interest in a topic declines much faster today than it did ten years ago. But that also means the window of opportunity for correcting misinformation or holding its originator accountable is closing faster. “And clever actors simply move on to the next topic quickly enough,” the cognitive scientist says. “But if you garner more attention with misinformation and get away with it without being held accountable, that creates incentives to lie.”

Profit at the cost of democracy

What makes Facebook, X & Co. so dangerous was by no means the initial goal of their developers, the researcher explains. The business model and algorithm were originally driven by technological development. “If Mark Zuckerberg had come along in 2005 and said, ‘I’m building a machine with which we can make money by showing people things that turn them against each other and undermine democracy,’ they would have called him crazy and said, ‘Go home and don’t come back!’” The largely unchallenged monopoly position of Meta, Google, or X alone ensures that there seems to be no turning back from the path taken. “If you can maximize profits by destroying democracy, then that’s not going to stop Facebook,” is Lewandowsky’s sobering assessment.

But it is no longer just ruthless business models that are undermining fundamental democratic values, as the researcher emphasizes. “The biggest threat to democracy is literally billionaires who have decided that democracy is not in their interest. And they have an incredible amount of money and power—access to the social media industry, which is basically a surveillance industry – an industry that is being used to abolish democracy.” There is clear evidence that X’s algorithms were changed after the takeover by Elon Musk to suppress the political messages of the Democrats and favor those of the Republicans. There are indications of similar influence on the federal elections in early 2025. In any case, Elon Musk openly used the platform after its takeover in fall 2022 to support Trump’s election campaign. “We have to assume that Musk is significantly changing the algorithm to essentially favor the extreme right. I think X is not a social network, but an instrument. We live in an Orwellian world.”

The political will to change something

Lewandowsky does not consider this development to be irreversible. “I am convinced that we need to look at the business model behind the networks and, as a democracy, take control of it – or at least find a way to make it work for society and not against it.” Filtering out hate, lies, and misinformation has already worked – many companies had been doing it for years before X, Google, and Meta recently abolished it as a supposed restriction on freedom of expression. But what if we went further? What if advertising were banned on these platforms and they had to finance themselves through subscription fees from their users? “That would change everything,” he says. “Suddenly, it would be in the interest of social networks to keep users away from the platform because then they would save resources such as server and personnel costs.” It would also be possible to place social networks under public control and offer them as a service for everyone, similar to public broadcasting. Both are just ideas at this point, which should be discussed at the political level, according to the researcher. “But it takes political will to change things. Because we are in a race against the dark forces.”

Prof. Lewandowsky himself is working together with partners in the PRODEMINFO project to develop concrete strategies against the advance of misinformation. To this end, the team is developing instruments that are intended to “immunize” people against misinformation and its influences. One approach is the principle of “preventive education.” “We help people recognize that sincerity is not always synonymous with truth and encourage them to question their intuition.” Initial studies on this have yielded promising results. “Then they become less tolerant of violations of norms, for example by politicians, and do not let them get away with false information so easily.”

PRODEMINFO – Protecting the Democratic Information Space in Europe is an Advanced Grant from the European Research Council (ERC) that aims to gain a better understanding of how truth is perceived in an age of fake news and conspiracy theories.

You can visit the PRODEMINFO website here: https://www.uni-potsdam.de/en/prodeminfo/index

Meta Platforms, Inc. is a US technology corporation focusing on social networks such as Facebook and Instagram.

Google is a web search engine owned by the US company Google LLC. Since 2006, the company has also owned the interactive video portal YouTube.

X, known as Twitter until July 2023, is a social network launched in 2006 as a short messaging service by Jack Dorsey and others. In October 2022, the service was taken over by X Corp., a company majority-owned by Elon Musk. X is now one of the most visited online platforms in the world.

This text was published in the university magazine Portal - Zwei 2025 „Demokratie“. (in German)

Here You can find all articles in English at a glance: https://www.uni-potsdam.de/en/explore-the-up/up-to-date/university-magazine/portal-two-2025-democracy