“Archives collect and preserve documents because they have a legal mandate to do so,” explains Ralf Müller. “Unlike libraries, they don’t focus so much on books: In the archive, we have papers that document the written tradition of the university. They are not for sale, and we don’t lend them out.” Since 1991, when Müller was 30 years old, he has been head of the university archive. It’s a bit as if he had been there for much longer and present when the first student enrolled at the Brandenburg State University or when Joe Biden met with a professor at the Academy of Political Science and Law – but more on that later. The 64-year-old is extremely well-versed in German-German history, but he also knows the stories of everyday life in the post-war period, the GDR, and in the early years of reunification just as well.

Archive instead of Alzheimer’s

“Archives are the long-term memory of a society. And we are the memory of the university. If we are neglected, then the university may get Alzheimer’s,” Müller says and laughs. In the 1980s, he studied history and archival studies at Humboldt University, then worked as a historian. During the reunification period, he and colleagues ensured that documents from the Ministry of State Security (MfS) of the GDR were transferred to the Stasi Records Archive in Berlin and secured there. “Archivists were supposed to prevent misuse of sometimes sensitive documents at that time.” This is why there are no documents in the university archives of the written legacies of the Academy of Law of the Ministry for State Security, which was based in Golm until 1990. “They fall under the Stasi Records Act.”

A lot of daylight gets into the large room through the windows. That is actually not ideal for paper, explains Robert Fröhlich, an archive employee. This is because sunlight can leave unsightly shadow imprints on the documents. But fortunately, they are well packed in ISO-standardized cardboard boxes. “We need temperatures of 16-18 °C and humidity of 30-50 %,” Fröhlich explains. “The climate must not fluctuate too much. This way, the paper will hopefully last for the next decades or, in the best case, for centuries.” The Golm location is actually a temporary solution, Müller says. Where there was a restaurant of the law school in GDR times, more than 150,000 student files from 1948 onwards are now stored, including certificates and records. In addition, the Division of Student Affairs keeps the final theses of the past five years here, which is mandatory by law. There are no deadlines for certificates and records. They remain in the archive for an unlimited period of time.

“Should you ever get into the situation of misplacing your certificate, we can issue a certified copy,” Müller says. Especially after the fall of the Berlin Wall, there were a large number of inquiries because former students of the GDR had to prove their social insurance history. “Sometimes students came here who had graduated in the GDR but then went to the West,” Müller says. “Of course, their certificates were not forwarded to them by mail.” In addition, there are the “sentimental requests,” as Müller calls them: from time to time, former students look for fellow students from their seminar groups at the College of Teacher Education. “We can sometimes help here – to the extent permitted by the protection of personal documents,” Müller says.

Rare finds

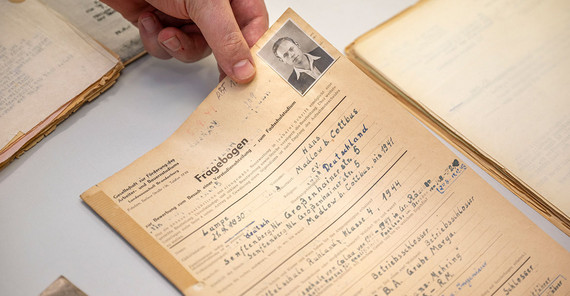

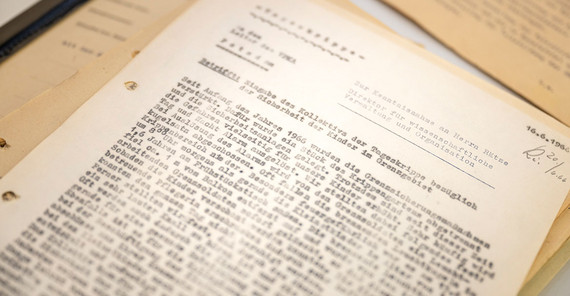

The two archivists have set up a smorgasbord of documents on the tables in the entrance area. A place that, despite the stuffy air, the dead paper, and the silence, is full of life: of stories from many decades, of people who have studied or researched at the university or visited it. There is Hans Lampe, born in 1930, who went to school for only four years. The trained locomotive fitter studied at the Potsdam Workers’ and Farmers’ Faculty – but he dropped out due to “challenges with the subject matter.” “At that time, the aim was to break the bourgeois monopoly on education and also give children from working-class and farming backgrounds the opportunity to study,” the historian explains. These faculties existed until 1964, but Müller and Fröhlich still receive inquiries from former students from time to time.

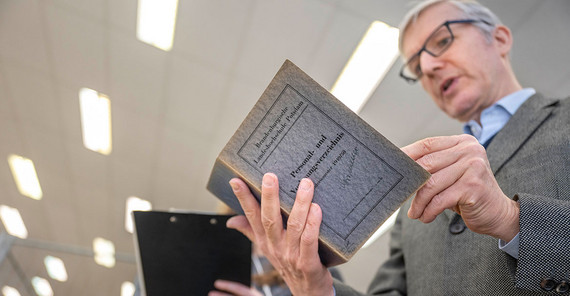

On the table there is also a staff directory of the College of Teacher Education from the academic year 1949/50, listing the private addresses of all lecturers. Notably, many of them lived in Berlin even then! Some even commuted from Berlin-Buch to Potsdam. The first rector, Arthur Baumgarten, can also be found here. “As far as teacher training was concerned, the College of Teacher Education was the most important institution in the GDR,” Müller explains. As early as 1966, the college established a university archive – the predecessor of today's university archive.

Another find shows the construction plans that existed in the 1970s for the Campus Am Neuen Palais. A real university town would have been created there, with dormitories and buildings for research and teaching at Sanssouci Park. While planning new buildings in the GDR was quite uncomplicated, implementation was often a problem – building materials or machinery were too often lacking. Today it is exactly the opposite, says Müller, with regard to quite a number of construction projects that have remained stuck in their initial stages due to lengthy administrative processes.

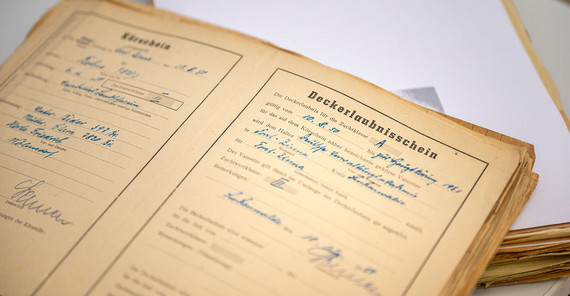

Another curiosity is the “licensing and breeding permit” for Bolus, the breeding boar in Griebnitzsee. “These are the small, everyday stories that we preserve here,” Müller says with a smile. Next to it, there is a letter from 1966: The director of the Babelsberg day nursery, which belonged to the Academy of Political Science and Law, thought that the children were disturbed by the proximity to the West Berlin border. “The lady was upset about the fact that children were constantly frightened off by flares or gunshots.”

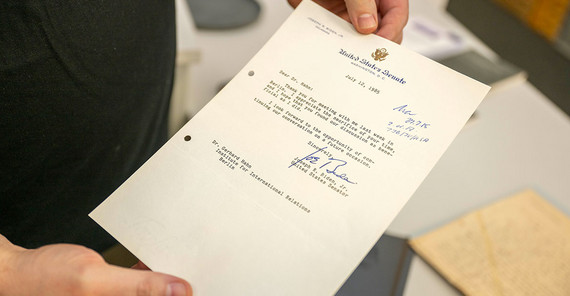

One of Robert Fröhlich's favorite pieces is an inconspicuous sheet of paper that is bright white compared to the other documents – a letter of thanks, signed by former US President Joe Biden. In 1985, as the “highest-ranking politician” in the Senate Subcommittee on European Affairs, he met Prof. Dr. Gerhard Hahn, the director of the Institute of International Relations at the Academy of Political Science and Law. “Not many universities have such a document in their archives,” Fröhlich suspects, beaming.

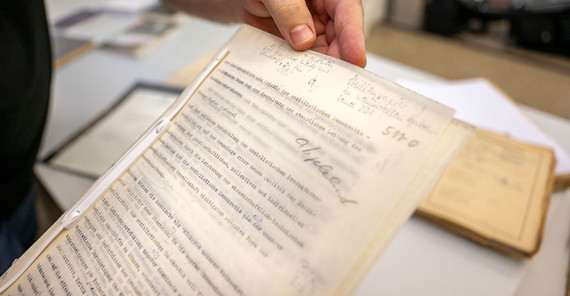

Ralf Müller also has a favorite piece: on a semi-transparent, wafer-thin piece of paper, a manuscript for the academic journal of the Academy of Political Science and Law, the editor-in-chief wrote in the 1980s: “Sandwich paper in the top industrial country GDR.” Müller finds that this reflects the mood of the time. “Of course, he knew exactly that no one would get to see it except him and maybe his secretary, but the poor paper quality must have really annoyed him since he wrote down this remark.”

GDR art in the basement

There would also be a lot to discover in Griebnitzsee if the warehouse in the basement of House 1 were not being renovated at the moment. Thousands of exam files are stored here, but also a lot of art: There are busts of Walter Wolf and Albert Einstein and also the “legendary Karl Liebknecht bust, which until 1990 was enthroned in front of the big lecture hall of the College of Teacher Education,” as Fröhlich knows. There are also some paintings, for example by the aforementioned Arthur Baumgarten, the first rector. Or a painting showing students “learning on their own,” with the colonnades in the background. It was painted by an art teacher from the College of Teacher Education. In another painting, students are seen harvesting – a typical picture for the time, Müller says. “Anyone who wanted to study in the GDR had to complete a harvest assignment beforehand. I was still picking apples in the Havelland region in my fourth year of study.”

When someone offers documents to the archive, Müller first checks them for their “archival maturity” and “archival worthiness.” Do they document the activities of the institution? Is there a so-called registry connection? Do they have a historical, cultural value? Are there legal reasons for keeping them? If so, the documents get a signature and are entered into the database. To prevent rust stains, Müller “demetallizes” them and removes paper clips and staples. The documents are then packed in boxes and sorted into the stacks. “This work can sometimes be unpleasant,” Müller says. But time and again, touching stories are hidden here: such as the telegram of parents searching for their daughter, who did not come home for Christmas – because she had apparently fled to the West.

The reunification years were “wild years of upheaval,” also for the archive. The Academy of Political Science and Law, which was renamed “University of Law and Administration” in 1990, was liquidated relatively quickly, Müller says. “At that time you often heard: The office has to be handed over swept clean by tomorrow 12 o'clock because a new professor is coming. Sometimes the cleaning staff informed us about it in advance, and my colleague at the time and I then went there with a laundry basket and secured masses of documents,” the historian says. “When a state suddenly ceases to exist, the employees of an institution no longer necessarily feel obliged to hand over their documents to the archive in an orderly manner.”

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree

Robert Fröhlich is a specialist in media and information services. He completed his training at the Stasi Records Archive. Both are “genetically predisposed,” Müller and Fröhlich say with a smile: Their parents already worked in archives and as historians. Why does Müller like this work? “It has an investigative touch that should not be underestimated. I like to get to the bottom of things or look behind the scenes, and this is what I can do here.” Sometimes this almost resembles a Sisyphean task. Fröhlich can tell you a thing or two about this: In a major digitization project, he has already scanned and tagged 40,000 of a total of 115,000 photos from 1948 to 2003. It was not always easy to find out who can be seen in the historical pictures. “For this ‘Who’s Who’, the university news was a very good source,” Fröhlich says. After all, the predecessors of the university magazine date back to the time of the College of Teacher Education.

Today, more and more documents are being created as “born digital”. Since the summer semester of 2022, students have had to submit their theses only in digital form. The area of documents from the Department of Student Affairs will gradually be emptied. The situation is similar with student files, which have been digital since the summer semester of 2023, although certificates and records still go into the archive in paper form. Müller and Fröhlich want to transfer the digital files to a so-called archive server, in a special PDF archive format that can be read for a long time. “We are currently in a phase of change. At some point, our archive will also be faced with the question of what still ends up here and in what format. That makes our time exciting.”

For now, however, the two archivists still rely on paper. Most of the documents they keep here are unique pieces without digital copies. “As unimportant as a document may seem, if it is only available once, then it is unique,” Müller explains. And paper doesn’t blush. But after 100 years at the latest, it has to come to an end – assuming it was of high quality. “We don’t have enough experience with printed paper yet: We don’t know what the lifespan of documents created with inkjet or laser printers is,” Fröhlich says. In principle, however, the collection has eternal status, Müller explains. At the end of 2026, he will retire after 35 years – but the stories will remain, well preserved in the university archives.

Ralf Müller has been head of the Potsdam University Archive since 1991.

The Potsdam University Archive preserves students’ personal and examination files, staff documents, and subject files regarding the University of Potsdam and its predecessor institution, as well as the institutions from which it assumed property: Potsdam/Brandenburg State College of Teacher Education (1948-1990/91), Workers’ and Farmers’ Faculty Potsdam (1949-1964), Rosa Luxemburg Institute for Teacher Education Potsdam (1964-1990/91), Institute for Teacher Education Clara Zetkin Cottbus (1948-1990/91), Academy of Political Science and Law of the GDR (1949-1990) and University of Potsdam (1991 to present).

Every student has the right to inspect his or her own file. But according to the law, third parties are also allowed to inspect the documents with the consent of the person concerned. If this person has already passed away, a period of ten years after the date of death applies, or, if this cannot be determined, 90 years after their birth. In cases of special public interest or in the context of scientific projects, these deadlines can also be shortened at the discretion of the archivist.

www.ub.uni-potsdam.de/de/ueber-uns/universitaetsarchiv

More information on the history of the university and its sites

https://www.uni-potsdam.de/de/zeitzeichen/standorte/griebnitzsee/die-universitaet-potsdam

This text was published in the university magazine Portal – One 2025 “Children” (PDF).