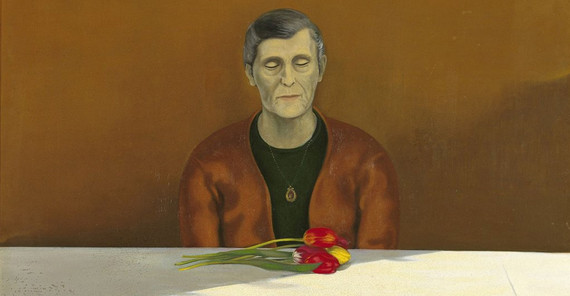

Anyone who went to school in the GDR in the 1980s had to write a reflection on this picture in art class. They could reflect on the role of the working woman, on double and triple burdens, also on loneliness. Once again, a work of art stimulated a social debate on topics that were either ignored or deliberately concealed in the state-controlled GDR media.

After Mattheuer’s painting “Die Ausgezeichnete” disappeared into depots and archives as a result of reunification, like many other pieces of art from the GDR, the painting is now shown again for the first time in the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. The exhibition “Extreme Tension. Art between Politics and Society – Collection of the Nationalgalerie 1945-2000” includes a number of works created in the GDR, including works by Uwe Pfeiffer, Harald Metzkes, Angela Hampel, and Strawalde.

Franke calls the contrasting juxtaposition of art from East and West experimental and bold. The Potsdam Professor of Art History in School Teaching and Learning Contexts has dealt in depth with “Self-narratives and traces of upheaval in the oeuvre of artists from the GDR” and published art-historical contributions on the topic in an anthology. It also includes a conversation between Franke and the Deputy Director of the Neue Nationalgalerie, Joachim Jäger, who sees the inclusion of works from the GDR as an enrichment, above all “because we no longer look at the development of art exclusively under certain ‘isms’ but perceive it as more varied, more complex, and more multi-layered.” In the GDR, very serious questions about life were discussed in art, theatre, and literature, always revolving around the existential question of conditio humana – “perhaps because the cultural workers did not live in a free society, but in a dilemma,” Jäger says.

Self-empowerment in times of surveillance

While the exhibition shows the differences in thinking and acting in two political systems and the differences with regard to media, styles, and themes, in particular the conflict between “figurative” and “abstract”, there was a convergence in the 1980s, says Jäger, citing the performative works of Cornelia Schleime as an example. Her crouched naked body wrapped in barbed wire, her face tied up with coarse ropes, or the plastic bag pulled over her head – it is these self-stagings, captured photographically, that make you feel the threatening narrowness and take your breath away when looking at them.

Schleime, whose work had been defamed by GDR officials as “garbage art,” told her life story as that of resistance and consistently inscribed the role of the rebel into her artistic biography, the Frankfurt art historian Viola Hildebrand-Schat sums up. She has taken a closer look at the performances and overpainted photos of the East German artist and contributed a text to the anthology.

A large part of the book edited by Franke results from a conference which she hosted at the University of Potsdam in 2024. The discussion mainly focused on “what role biographical self-reflection plays in shaping artistic developments and turning points,” says the art historian, who heads a research project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation Bern on “Images of History in Contemporary Art.” All texts in her book seem to have one thing in common: the search for the conditionalities of the individual and the social sphere, of personal imprints and historical events, of the private and the political, which find their expression in art. For example, in the work of the Spanish painter Núria Quevedo, who fled as a 14-year-old with her mother from the Franco dictatorship to the GDR, where her father was already living. Based on Quevedo’s painting “Thirty Years of Exile” (1971), the American art historian April Eismann searches for the biographical traces of the artist in the warm and dark, almost monochrome paintings. It is the story of flight and migration, of arriving and remaining a stranger – whether “Bildnis meiner Mutter” (Portrait of My Mother) (1973), “Die Ahnen” (The Ancestors) (1970), or “Erinnerung” (Memory) (1981). Quevedo painted the dining room of her childhood in Barcelona in this picture, the table where she did her homework or played with her sister. The calendar page on the wall shows the day the girl had to leave Spain. Even if you paint still lifes or landscapes, Quevedo says, it is “your own biography that you paint again and again.”

“Radikale Intimität” (Radical Intimacy) is the title of Luise Thieme’s contribution, in which she deals with forms of self-empowerment in the works of Gabriele Stötzer and Tina Bara, two artists who were exposed to extreme surveillance and spying by the Stasi. Thieme, who researches artistic-feminist practice in the GDR at the University of Jena, shows how the two women used alternative art spaces to resist and oppose their external assessment through their own strong selves. Bara did this in over four hundred black-and-white photographs from the 1980s, which were published in the photo book “Lange Weile” (Boredom / A Long While), Stötzer with the Super 8 film “… hab ich euch nicht blendend amüsiert” (... Haven’t I amused you brilliantly). The film documents the transformations during a self-painting, the associations of which, according to Thieme, also refer to the repression and physical heteronomy that Stötzer experienced in prison.

The Berlin art historian Angela Lammert provides surprising insights about the “black pictures” in the former coal cellar of the Berlin Academy of Arts on Pariser Platz. “Testimonies of a youthful post-war awakening in Berlin painting,” Lammert calls the pictures that were scratched, painted, and drawn on the occasion of two carnival festivals in and on the walls before the Wall was built. The protagonists were the then-young master students Manfred Böttcher, Harald Metzkes, Ernst Schroeder, Werner Stötzer, and Horst Zickelbein, whose murals are “nonchalantly and ironically” reminiscent of Pablo Picasso and Bernard Buffet, according to Lammert, who in her text invites us to look at the “black pictures,” and not only them, with and from an international perspective. “Because self-expression as a form of knowledge is not only a characteristic of art in the GDR.”

Devaluation of revolutionary desire

On the other hand, “Spurlos” (Without a Trace), the last mail art action from the GDR, which the artist Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt combined in 1990 with the urgent call to “speak out for the preservation of the social rights and the positive intrinsic values of the GDR and to vote against the hasty abolition of the GDR’s independence and its appropriation – of whatever kind – by the FRG,” shows a clear reference to place and time. The doctoral student Marie Eggert, who researches the relationship between art and politics, investigated this particular form of protest, in which small-format graphics with political messages were posted internationally with the request to send them back to a public addressee, in this case to the German Bundestag and the East-German parliament Volkskammer. It is possible, Eggert writes, that Wolf-Rehfeldt’s last mail art campaign was, because of the rapid political developments, designed from the outset to result in its own lack of trace.

It is precisely in this lack of traces and speechlessness, in the devaluation of revolutionary desire, and the very special democratic forms organized bottom-up, that the artist and author Elske Rosenfeld sees a cause of East German expressions of displeasure, which for decades were dismissed as “politically irrelevant” and “mere whining” and are only now taken seriously since they have increasingly taken place under right-wing auspices. In the anthology, Rosenfeld expresses this in a conversation with Burak Üzümkesici, who researches political forms of action and artistic practice at Freie Universität Berlin. With different historical perspectives and socializations, Rosenfeld and Üzümkesici talk about artistic approaches to “revolutionary gestures” and “militant images,” political stages, the physical experience of social upheavals, and their failure.

When Rosenfeld talks to people who were involved in the reunification period of 1989/90, she feels the “excitement about what seemed possible at that time, the sadness and anger about the loss of these new political opportunities, which seemed to be in reach for a short time.” She recognized the same gestures in activists of the Arab Spring, the protests in Gezi Park in Istanbul, the uprisings in Ukraine and Belarus. From the “surprising resonances” between what she has experienced in different contexts at different times and places, she tries to develop a common gestural vocabulary. Documentary material forms the starting point for her work on an “Archive of Gestures.”

The anthology, edited by Franke, illustrates from various perspectives how such an archive – as well as art and the events it narrates – can contribute to a better understanding of history.

Melanie Franke has been a Professor of Art History in School Teaching and Learning Contexts at the University of Potsdam since 2021.

This text was published in the university magazine Portal - One 2025 “Children”..