Characteristical experiments

Reading Experiment MW (Moving-Window-Technique)

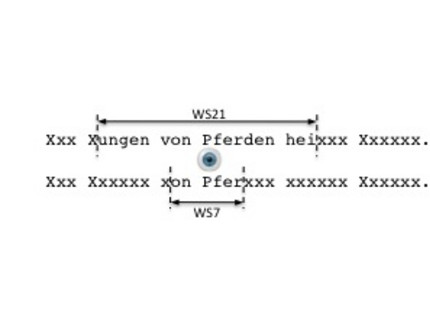

Children read single sentences on the monitor screen while their eye movements are continuously tracked. Because we sample the eye position 1000 times per second we know exactly which word or even letter a child is currently fixating. This allows us to experimentally manipulate the child’s reading fluency, by imposing a window around its current fixation, thus restricting its effective field of vision. An example is shown in figure 1. For instances a window size of 21 letters means that the currently fixated letter as well as 10 letters to the left and right respectively is visible, while the remainder is masked with Xs. In other trials the window can be as small as only 7 letters. With smaller windows participants typically read slower, fixate and regress more often, initiate shorter saccades and skip fewer words. When comparing different grades, the “typical” reading behavior of first-graders is less affected by smaller windows than that of second- or third-graders. This is because first graders tend to read foveally, i.e. letter-by-letter, whereas with higher reading proficiency children start to also extract meaning from the parafovea, i.e. from words that are not fixated (roughly speaking). To estimate the size of the perceptual span, i.e. the visual field, where information can be extracted during a fixation, we calculate at which maximal window size children won’t read faster. A comparison between first, second and third-graders can be seen in figure 2. The size of the perceptual span in German first graders is about 4 letters to the right, for second-graders about 5-6 letters to the right, and for third graders about 7 letters to the right. English speaking graduates have actually been found to have a perceptual span size of about 14-15 letters to the right.

PIER study

How efficient is first-grader’s word decoding compared to third grader’s decoding skill? What are causes that some children become high proficient readers and some don’t? Is it the specific academic environment or inter-individual differences in working memory, reading amount or motivation? How is reading comprehension on word, sentence and text level linked to reading fluency?Reading is a central cultural cognitive ability that children acquire during elementary school. As members of the DFG-founded longitudinal PIER study, Anja Sperlich and Johannes Meixner under supervision of Dr. Laubrock track German abecedarians reading development from first to sixth grade and beyond. With the help of the Eyelab they precisely measure the children’s eye movements during natural reading, inferring how long it takes to decode words of varying difficulty, which parts of a sentence need to be re-read and which parts are skipped. The focal point of investigation is the perceptual span, i.e. how much linguistic information can be processed during one fixation. The longitudinal design of the study and the comprehensive PIER data set on motivation, emotion, memory and cognitive competencies, enable them to identify risk- and protective factors that influence reading development. They already found that lexical decoding is an influential precursor of perceptual-span development during the first three grades. If you are further interested we highly recommend reading Sperlich, Schad & Laubrock, 2015. The journal article offers an overview of the perceptual span development during the first three grades of elementary school.