1. The Roman Empire or ancient Greece?

Both. I also like dogs and cats.

2. What sparked your interest in antiquity?

Even as a child, I was fascinated by mythology and the idea of communicating with long-gone eras.

3. What are you currently researching?

This summer, I want to finish a small book on bilingual teaching; my next major project will be an overview of ancient historiography.

4. From 2004 to 2018, you taught Latin and Greek at a high school in Basel. What drew you to the university?

I never really left the university—what made the difference was being offered a permanent position, while the situation at school was always precarious due to the small number of students in my subjects.

5. What would you be today if you weren’t a professor of classical philology?

An art historian. I actually wanted to pursue a PhD in art history, but then I got a job in Greek studies. Well.

6. You live in Berlin and commute to the University of Potsdam like most of the students. How do you use your time on the train?

Depending on how I feel that day, I answer emails, read, or take a nap.

7. Basel or Berlin, what’s more livable?

It depends on your priorities: Do you prefer a functioning administration or the excitement of a capital city?

8. Can ancient texts tell us something about ourselves as modern people?

We always find ourselves in all texts. But the more distant a text is from us, the more clearly we perceive our own time-bound nature.

9. Do these historical constants suggest that there is such a thing as unchanging human nature?

You might have to ask a philosopher. But of course, ancient texts also speak of emotions that still concern us today.

10. In the spring, the University of Potsdam joined the Berlin Antike-Kolleg (BAK), an association of ten research institutions. What is the purpose of the BAK?

The BAK offers us completely new opportunities for networking and exchange, for example with Egyptology, archaeology, and ancient Near Eastern studies. Classical philology can only benefit from this.

11. And what role does the University of Potsdam play in this?

We participate in major research projects. For example, I am part of a group working on the construction of reality in ancient worlds.

12. Where is the journey supposed to go – what do you hope to gain from the collaboration with other universities and research institutions?

I am already receiving a lot of input for my own research. In the future, we hope to secure positions for early-career researchers.

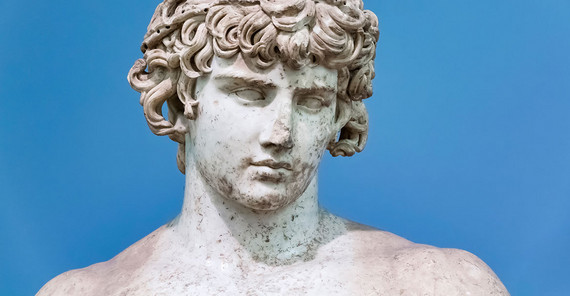

13. Currently, many right-wing groups use Greek and Roman symbols, and on X many cultural-pessimist accounts feature ancient statues as profile pictures. What is the message behind this?

Everything used to be better: everyone was as white as a marble statue, and men were in charge.

14. In your essay "Warum Antike?“ (Why Antiquity?), you recommend careful reading as an antidote to such appropriations. What can we learn from this?

If you look closely, you will almost always find complexity rather than simplistic worldviews.

15. In May, you moderated the panel discussion "Researching under a dictatorship? How anti-democratic movements threaten science." The humanities in particular are under pressure. Do you think that your field is at risk?

Classical philology is not as much in the focus of anti-democratic actors as climate research or gender studies. But threats to academic freedom concern us all.

16. Does research need democracy?

Of course, research needs open, fearless debate and a transparent culture of failure.

17. Do you think AI can be helpful in your field of research?

At the moment, AI is a double-edged sword because it is so unreliable. Today it produces an error-free Latin text, tomorrow complete nonsense. But it is certainly fascinating to see the thought patterns it works with.

18. Which historical cliché would you most like to erase from collective memory?

That the ancient Greeks were somehow better people.

19. Do you have a favorite poem, ancient or otherwise?

It’s hard to choose. High on the list is certainly Catullus’ Attis poem, about a young man who becomes a woman in the service of the goddess Cybele. The subject matter is extremely compelling, and the language is incredibly beautiful.

20. Have you ever dreamed in Greek or Latin?

No, I haven’t.

21. Do you have a favorite translation of the Odyssey?

I find Emily Wilson’s new English translation very interesting. But the Greek original is still highly recommended.

22. Printed book or e-book?

E-books are so much more practical – but the reading experience is simply different with a printed book.

23. Recently, the meme "How often do you think about the Roman Empire?" went viral. How often do you think about the Roman Empire?

Quite often, due to my profession.

24. The subject of antiquity is a constant source of inspiration for pop culture. Do you see this as positive, or does it cause damage that is difficult to repair?

No, it’s great. It’s wonderful that past eras continue to capture people’s imaginations.

25. Besides Greek and Latin philology, you also studied art history. Does art history still influence your research today?

I think a lot in images, and I constantly re-examine the art-historical reception of ancient narratives.

26. In 2021, you published your book Die abgetrennte Zunge: Sex und Macht in der Antike neu lesen (“The Severed Tongue: Rereading Sex and Power in Antiquity”). Have the last three millennia seen enough progress in terms of equal rights?

The systematic discrimination of women (as well as queer and migrant people) is probably one of the fundamental anthropological constants we have to live with. At least we – still – live in a time when this issue can be openly discussed.

27. Since 2005, the Chair of Classical Philology has organized the annual Potsdam Latin Day, which is popular with teachers and students alike. What can participants expect?

Exciting lectures and workshops: this year on the topic of “Plural Antiquity: Migration, Multilingualism, Multiculturalism.”

28. Will Latin remain a relevant school subject, even though fewer and fewer students have chosen it as a foreign language in recent years?

I hope so – and I actually believe it will. The classical language community in Germany is very lively and committed.

29. Is there a researcher you particularly admire?

Many. What has always impressed me is the reconstruction of early Greek poetry from papyrus fragments by researchers such as Denys Page, Edgar Lobel, and Eva-Maria Voigt. This combination of perfect command of language and metrics, on the one hand, and creative imagination on the other, leaves me almost speechless.

30. What gaps in your field would you most like to see filled?

It’s amazing how many important ancient texts still lack scholarly commentary. There is still a lot to be done.

31. Do you prefer research or teaching?

The combination is ideal – I really enjoy speaking about my research, and I also get a lot of inspiration from students. But every now and then I need some peace and quiet to develop everything.

32. What would you research if you had unlimited resources at your disposal?

I would research the classicist image of antiquity in the 19th century – starting with scholars such as Friedrich August Wolf and Wilhelm von Humboldt, whose views continue to shape school teaching to this day.

33. When you’re not researching or teaching, what do you enjoy doing most?

Unfortunately, nothing spectacular: meeting friends, hiking, cycling, eating, drinking, visiting museums, swimming, listening to music, going to the movies – just the usual stuff.

Katharina Wesselmann has been Professor of Classical Philology at the University of Potsdam since 2023.

This text was published in the university magazine Portal - Zwei 2025 „Demokratie“. (in German)

Here You can find all articles in English at a glance: https://www.uni-potsdam.de/en/explore-the-up/up-to-date/university-magazine/portal-two-2025-democracy